In a 1988 music video, Vermont comedy duo Gould & Stearns sang, "Vermont is a third-world country (but the people don't know)." Provocation? Perhaps. But that statement evokes a contradiction at the core of our state's identity: The way of life that, for many, has bestowed Vermont with its particular charm is an endangered one.

That same paradox resonates in the images of Vermont photographers Richard W. Brown, Ethan Hubbard and Peter Miller. Each has devoted his time and talents to chronicling Vermont's changing — and disappearing — ways of life, capturing privation and hardship alongside natural beauty. While Peter Gould and Stephen Stearns delivered their message about the state's economic and cultural shifts in a wacky, over-the-top format, Brown, Miller and Hubbard strike a far more nostalgic and somber tone.

"[Photographing in Vermont] really was, to me, like getting in a time machine," noted Peacham-based Brown. His book The Last of the Hill Farms: Echoes of Vermont's Past, designed by his wife and Vermont Life art director Sue McClellan, was released this fall; he'll speak about it at the University of Vermont on Wednesday, December 6.

Over the summer, Miller published his sixth book, Vanishing Vermonters: Loss of a Rural Culture. The Waterbury-based writer and photographer has practically made a career of documenting the state's rural identity since the 1990 publication of his iconic Vermont People.

A retrospective of portraits taken by Hubbard, who lives in Washington, Vt., is currently on view at the Vermont Folklife Center in Middlebury. Many of the images in "Driving the Back Roads: In Search of Old-Time Vermonters" appear in his 2004 book Salt Pork & Apple Pie: A Collection of Essays and Photography About Vermont Old-Timers, available for purchase at the exhibition.

While each has his own angle and style, Brown, Hubbard and Miller also have much in common. Now all past the age of 70, they came from urban or suburban communities in the Northeast and settled in rural Vermont. They took their early photographs on black-and-white film. Generally speaking, their images belong to that category of documentary photography that sits — sometimes uneasily — between art and anthropology.

Occasionally, even the photographers' subjects overlap. Waterbury dairy farmer and filmmaker George Woodard appears in both Miller's Vanishing Vermonters and Hubbard's 2009 volume Thirty Below Zero: In Praise of Native Vermonters. Both Brown and Hubbard have given special attention to Theron Boyd (1902-90), a peculiar bachelor farmer in Quechee who refused to sell his property to developers. His homestead is now in the care of the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, slated for eventual opening as a historic site. The VFC plans to exhibit Brown's work in March 2018. "Ethan and Richard have very different approaches to similar subjects," wrote executive director Kathleen Haughey by email. "That contrast is interesting and worth exploring."

Tom Slayton, who served as editor-in-chief of Vermont Life magazine from 1985 to 2007, wrote the forewords to both Brown's recent volume and Hubbard's Salt Pork & Apple Pie.

"All of us who live here are concerned about the possible loss of Vermont's scenic beauty," Slayton said by phone. "I personally think it's tied very closely to Vermont's working rural culture. Vermont looks very different from the rest of New England because it's farmed ... Real work done on the land not only produces food, it produces a beautiful countryside."

What links these photographers, besides the format of the reverential documentary portrait, is the desire to capture a cultural landscape in which the small farm is no longer the dominant means of survival. Commodity farming, state regulation, economies of scale and fluctuating milk prices have made Vermont's traditional lifestyles difficult to sustain. While the state claimed more than 3,000 dairy farms in the 1980s, today just 900 farmers are milking cows, sheep or goats, according to the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets.

Haughey says Hubbard's combination of portraiture and stories has proved an especially popular exhibition. "It's been a rather tumultuous year in terms of politics and social stability," she said. "I think there's a bit of a nostalgia for past times, and people are interested in connecting to human stories. Seeing these old-time Vermonters can be a source of strength."

Seven Days spoke with Brown, Hubbard and Miller about their histories of rural image-making in Vermont and how they, having arrived "from away," decided to document their adopted home.

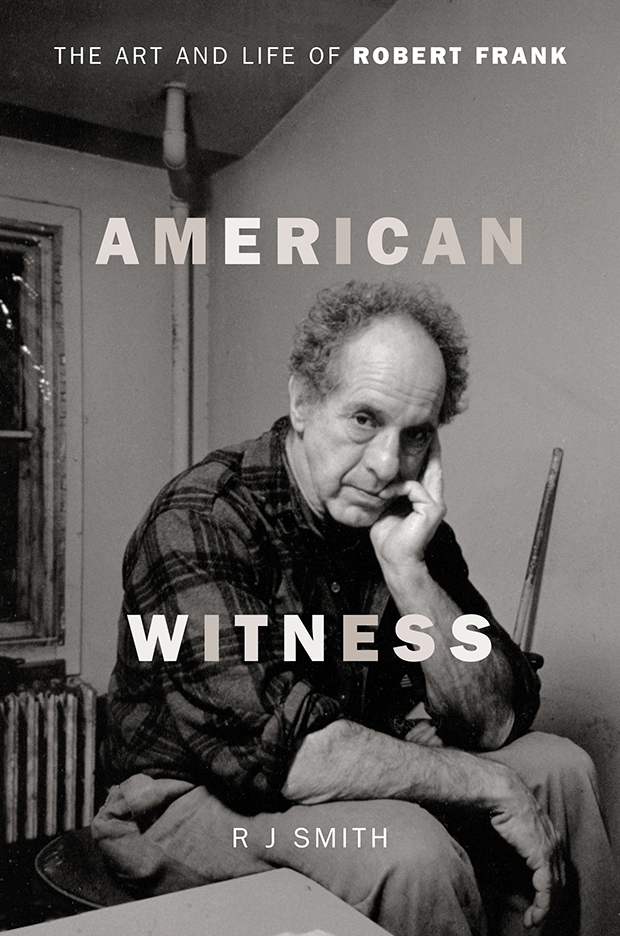

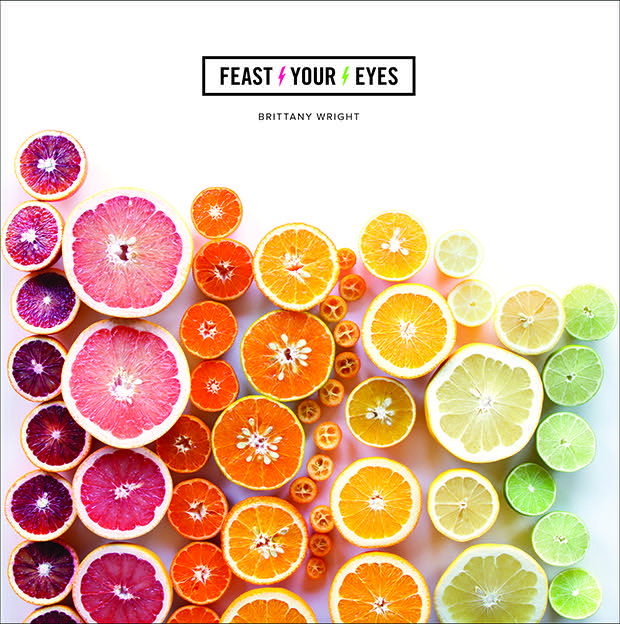

Richard W. Brown The Last of the Hill Farms: Echoes of Vermont's Past

When Richard W. Brown was still a student at Harvard University, he worked on a farm in Hartford. Driving through Quechee, he and a buddy saw a magnificent, crumbling old building. Thinking it was abandoned, they pulled over and got out to explore. They went from room to room, marveling at the structure that seemed to be from another era.

"We got into the so-called parlor," Brown remembered, "and my friend about fainted. He points, and I can see the back of this guy's head in a chair — he's asleep. God, did we get out of there in a hurry."

The "guy" was Theron Boyd, who would later become one of Brown's frequent photographic subjects. "It was 1975, and when I got out of my car, it was 1875," Brown said of his later work at the Boyd homestead. "It just kind of gave me goosebumps. And [Theron] was always glad to see me — I don't know why."

Raised in Wellesley, Mass., Brown would come to Vermont on family trips; his great-grandfather taught at Lyndon Institute, and his family had ties to the region. "I thought it was the greatest place I'd ever seen," Brown remembered.

Growing up, he intended to become a painter. In college, Brown purchased a camera to take on an African safari, thinking he would paint from the photos. Instead, he realized he preferred the medium of photography. Eventually, Brown armed himself with the same equipment that landscape photographer Ansel Adams used in the 19th century. Thus equipped, in 1971, when he was 25, he moved to the Northeast Kingdom town of Peacham "on a leap of faith."

"I wanted to be the Vermont version of one of those guys," Brown said, referring to Adams and his contemporaries. "I soon learned that that was a good way to starve." Brown would go on to make his living as a freelance commercial photographer, and more than 25 books of his photographs have been published in the U.S., Europe and Japan.

In the mid-'70s, Peacham was home to about 20 family farms, Brown said. Today, he knows of three or four. And "instead of milking 20 cows, they're milking 200," he observed.

Forty years ago, however, Brown didn't feel any sense of urgency about the state's cultural and economic transition. "I didn't think things were gonna change," he said, "and it took a while."

Most of the photographs in Hill Farms were taken in the 1970s. Brown's choice of subject matter and his aesthetic show his keen affinity for scenes of farm life that could have existed decades or even a century earlier. The photographer masterfully captures a striking range of tones and texture, crafting scenes that seem to expand and slow time the longer you spend with them.

"Richard has a poetic vision," Slayton said, adding that the photographer is a "master technician" who "seems to have an innate feel for Vermont's countryside."

"I like old stuff, that's my problem," Brown conceded. But, inexorably, things have changed. This fall, Brown attended a workshop in Barnet that was near some of his old haunts — "places where I could photograph four or five working farms," he said. "Now it's just trees."

In Peacham, he noted, the socioeconomic gap has widened considerably over the past few decades. In the '70s, he said, "There wasn't the sort of vast difference there is now. It was a pretty homogenous group in terms of income."

Brown acknowledged his weakness for rural romanticism. "In a lot of these places," he said, "I'm sure there were a lot of things that were very difficult, and some things that were not good. People having to struggle with making a living and all that.

"But, to look at, it was like an old painting by Eastman Johnson or Winslow Homer," he continued. "It was so beautiful. I don't know what else to say."

The Last of the Hill Farms: Echoes of Vermont's Past by Richard W. Brown, David R. Godine, 136 pages. $40.

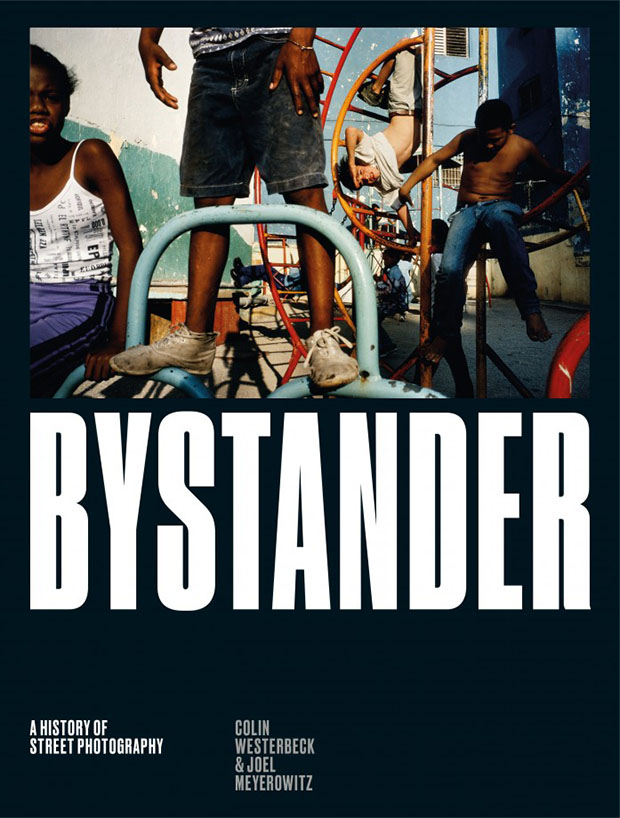

Ethan Hubbard Salt Pork & Apple Pie: A Collection of Essays and Photography About Vermont Old-Timers

In conversation, Ethan Hubbard cannot contain his deep and personal affection for "old-time Vermonters." The adoration seems to bubble right out of him.

Connecticut-born Hubbard moved to Vermont in 1964, freshly graduated from Rollins College in Florida, and took a teaching job at Waitsfield High School. Photographing Vermonters seemed to arise organically from his circumstances: A self-described "hippie," Hubbard had much to learn from the rural community in which he had planted himself, he said. Many of his subjects were, or would become, his close friends; Hubbard spoke in eulogy for East Brookfield's Keith Perkins in 2010, for example.

"They were so sweet to us hippies," Hubbard recalled of his neighbors by phone. "Those kinds of people were really good to the transplants who wanted to live a rural existence. We needed help. We didn't know shit about dry wood, didn't know how to barter ... We came here to be rural Vermonters, [so] who do we go to see? We don't go to Shelburne and ask rich people."

In one of the first portraits in Salt Pork, a bespectacled woman named Erdine Gonyaw holds up an apple pie she baked for the Albany town meeting. Hubbard described the photograph, which he took in 1969, as "a good picture of a sweet woman who was good to hippies." Indeed, Gonyaw has a patient, perhaps bemused, expression on her face.

Hubbard said his inclination to document his friends and neighbors resulted from early foresight. "I had a premonition that this breed of Vermonters was the last of the breed," he recalled. "I said to myself, Well, go out and photograph and tape-record as many as you can."

The photos in Salt Pork span from 1967 to 2002, many taken with a Canon AE-1 35mm camera. Leaving teaching behind, Hubbard worked as deputy director of the Vermont Historical Society from 1968 to 1977. That position allowed him to "drive the back roads" and collect more than 100 oral histories from folks he identified as old-time Vermonters. Excerpts from a few of those narratives accompany some of the 40 large-scale images on view in his current retrospective at Vermont Folklife Center.

After Hubbard left the VHS, he sold his Craftsbury property and used money he inherited to embark on travels that lasted 35 years and spanned some 60 countries. Occasionally he touched back down in Vermont, other times at his parents' home in Connecticut. Of course, he took his camera with him.

"I was doing the same thing as I did in Vermont," Hubbard said of his globe-trotting. "I fell in love with these old characters."

Over his career, he has published more than 10 books of photographs, including First Light: Sojourns With People of the Outer Hebrides, the Sierra Madre, the Himalayas, and Other Remote Places (1986), Grandfather's Gift: A Journey to the Heart of the World (2007) and "Me Like Goat Meat. Goat Meat Good, Mon": In the Company of Curiosities, Anachronisms, Misfits, Innocents and Angels (2011).

Hubbard's photographs of Vermonters stand out for their focus on joy. His subjects almost all seem to be smiling or laughing, as if caught while cracking a sly joke or sharing a fond memory. Unlike Brown and Miller, Hubbard eschews shooting sweeping landscapes or meditations on trees, graveyards and churches. For him, it's all about the people, and he usually frames them front and center, looking directly at the camera. Sometimes he catches his subjects in motion or a little out of focus, giving his images the intimate feel of a snapshot.

Hubbard doesn't call himself a writer, but in Salt Pork, as well as in exhibition text at VFC, he recounts time spent with his subjects in clear, sweet essays. In some cases, he acknowledges the perpetual hard work, poverty and loneliness in the subjects' lives. For the most part, though, Hubbard's stories shroud his "Vermont old-timers" in poetry and awe.

In contrast, he bemoans the fate of young people today. "They don't have balance. They don't know how to walk on a log in the woods," he said. His old-timers, he said, "were the last generation to grow up without television."

Hubbard, who does not have an email account or engage in social media, attributes much of the loss of old Vermont culture to a digital revolution that he wholeheartedly shuns.

"I'm outta here," he declared. "I'm out of the digital age. Good fucking riddance."

After Donald Trump was elected president, Hubbard said, he stopped using the term "native Vermonters." It felt "a little off-putting, a little pigeonholing," he said, decrying the general use of labels to sow divisions. It's worth noting that, with the odd exception (such as Hubbard's portrait of basket maker John Sweetser), true Vermont natives — the Abenaki — are not to be found in the collections of Hubbard, Brown or Miller.

Instead of "native," Hubbard has opted for "old-time Vermonters," measuring one's authenticity by the interval one's family has lived in the state.

"The people that I fell in love with have the lineage of 200 years," Hubbard said. "They've retained those special qualities of the mountains and the rivers and the communities and learning to do things [themselves]."

Of his beloved subjects, Hubbard offered, "They kind of chose me. These are a heartful people."

Salt Pork & Apple Pie: A Collection of Essays and Photography About Vermont Old-Timers by Ethan Hubbard, RavenMark, 129 pages. $19.95.

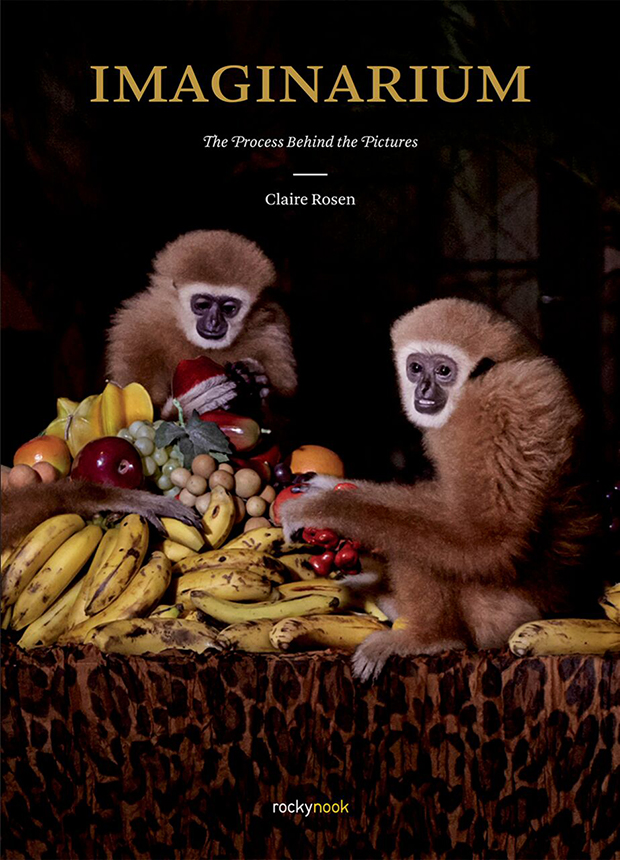

Peter Miller Vanishing Vermonters: Loss of a Rural Culture

Peter Miller's most recent book is dedicated to Romaine Tenney, a tragic folk hero of sorts whose story is well known by some, unknown to many. In 1964, faced with having to leave his 90-acre family farm in Ascutney to make way for the incoming Interstate 91, Tenney grabbed his rifle, lit all of his buildings on fire and died — most likely by self-inflicted gunshot — in the blaze.

Vanishing Vermonters is not a happy book. In some ways, it feels like a deeper, angrier, more urgent cut than Vermont People, the collection that brought Miller renown in the state. Though he struggled to find a publisher for Vermont People, it came to be a beloved staple, reprinted three times with multiple revised editions.

Miller moved with his family from Manhattan to Weston, Vt., in 1948, at the age of 14; he returned to settle permanently in Colbyville — a settlement area within Waterbury — in the 1980s.

In his earlier Vermont books, Miller demonstrated keen skills as both writer and photographer, the latter honed during military service in Europe, as an assistant to photographer Yousuf Karsh and as a journalist at LIFE magazine. The images in those books are distinctly art photographs, and their tone is, for the most part, celebratory.

Vanishing Vermonters strikes a different chord. It is overtly political, has a more journalistic bent and emerges not as a collection of nostalgic portraits but as a document of lives being lived in Vermont right now.

In his foreword, Miller declares the book "as realistic as the smell of skunk." It originated, he explains, in the responses to his 2013 book A Lifetime of Vermont People, as well as in two commentaries he published on VTDigger.org: "Cold Weather, Hard State" in March 2014 and "I Am Vermont Broke" in August 2016.

Those articles sparked plenty of online feedback, including heated debates on individual and governmental accountability and, Miller recalled, a lot of confirmation for his point of view. Many respondents lamented Vermont's high cost of living, which some said had caused them to leave the state.

"[These people] didn't have anybody in Montpelier, it seemed to me," Miller said, referring to the Vermont legislature. "So all of a sudden, it came to me: This is a book."

Vanishing Vermonters departs from the pattern of idealized portraiture and pastorals, instead combining some of Miller's carefully composed images with quicker digital snapshots. The weight of the work lies in the text. Miller has transcribed conversations with each of his subjects, who provide illuminating documentation of a broad range of Vermont experiences.

Not everyone featured was born in Vermont, and the subjects express no political consensus. Former governor Howard Dean is there alongside Trump voters. In fact, not everyone seems unhappy with the direction the state is taking. The commonality, Miller said, is that they are all "rural people."

"I let [my subjects] speak for themselves," he explained. "I put a few pictures in to show that I'm talking about something different that isn't necessarily beautiful."

Among the 20-odd profiles is one of Kim Crady-Smith, owner of Green Mountain Books & Prints in Lyndonville. Her family has been in Vermont for generations; she and her partner have no running water or electricity, and they sell their chickens' eggs at their store. "We joke about 2008 when the market crashed," Crady-Smith recalls in the book. "The economic crisis didn't really impact us because we [were] already poor."

The book's visuals include more than portraits. It's peppered with scenes of abandonment, such as a dilapidated house and an Irasburg hunting camp. Other pointed images include a sign protesting the Vermont Gas pipeline in Monkton, wind turbines in Lowell and a flattened can of Heady Topper.

Altogether, Miller's pictures, his introductions to his subjects and their verbatim reflections provide a nuanced view of a culture in flux.

Asked if he considers himself a "vanishing Vermonter," Miller replied, "I'm not really a Vermonter. I'm a woodchuck with a small 'w.' A woodchuck with a large 'W' is a native Vermonter. I'm an observer."

Vanishing Vermonters: Loss of a Rural Culture by Peter Miller, Silver Print Press, 168 pages. $24.95.

Source:

How Three Photographers View a Changing Vermont

Photographing Fall's sunshine

Photographing Fall's sunshine  Wildlife's photographer

Wildlife's photographer  Camera lens

Camera lens  Dawn in nature

Dawn in nature